The bright blue trailer is a lively addition to an otherwise standard school landscape at Dunaire Elementary in Stone Mountain. “C.A.F.E.”, written in bright yellow letters, is an acronym for the trailer’s purpose: Community Advocates for Education.

The effort — spearheaded by Justine Robinson, a retired 45-year-veteran of DeKalb County schools who now works as a part-time primary counselor at Dunaire — is designed to serve the school’s very diverse and ever evolving population.

“This community feels like it is a ministry,” said Robinson while giving me a tour of the school. “The school and the parents need support.”

Robinson came to Dunaire a few years after a tragic incident in which a student’s death by suicide inspired a 2011 state law that required local school systems to adopt policies on bullying and notify parents when their child is bullied or bullies someone else.

The school was high needs, low income and had social challenges. It languished as a low achievement school for years, but recently, Dunaire has been on an upswing, recognized for significant growth and improvement in literacy as well as positive changes to the school culture.

The demographics have also shifted. Almost 100% of students qualify for free and reduced lunch and 55%-60% are classified as English to Speakers of Other Languages. School staff and administrators have sought to make the school a safe space for its increasingly diverse community, said Principal Sean Deas who arrived in 2018.

“We had to shift the mindset in the building,” he said. “Kids were coming in with different stuff and the staff needed to change as well. This building is designed as a place of trust.”

Chastain Clark, an Atlanta based muralist, designed the Dunaire C.A.F.E. Clark enjoys helping students connect with art in different ways. Students enjoy both participating in the process of mural making and seeing themselves in the finished product, he said. Nedra Rhone/[email protected]

This is an important goal at a time when American concerns about immigration are at an all time high. In February, more Americans (28%) ranked immigration as the most important problem facing the U.S., according to a Gallup Poll. The last time immigration topped the list of resident concerns was in 2019, and the percentage of Americans concerned about it is higher than it has been since Gallup began collecting the data in 1981.

The sentiment is likely driven by the high number of southern border crossings in December and the movement of migrants into U.S. cities that has placed a strain on social services. The student population at Dunaire is often a reflection of those patterns. The school had a recent influx of students from Afghanistan and expects there may be an increase in the number of students from Haiti, Deas said.

About 20% of the students are homeless and many live in extended stay motels in the area. Though the community is transient, some families seek stability in the neighborhood so their children can continue learning at Dunaire, Robinson said.

When she conducted a survey to find out what parents needed most, the results were medical support, GED services and employment resources. The school district was planning to move an empty, unused trailer from the school campus but Robinson asked Deas if they could keep it and turn it into a parent resource center. Deas agreed but how could they do it with zero dollars?

Sue Sullivan was doing outreach through Decatur YMCA at a local extended stay motel when she met a parent from Dunaire. The parent kept mentioning Sullivan’s name to Robinson. When the two finally met and Sullivan visited Dunaire, the quiet and calm mood in the building and the melting pot of students from 29 different countries worked its charms. Sullivan began corralling resources and writing grants to help make the trailer happen.

Justine Robinson and Chastain Clark outside the Dunaire C.A.F. E. where families may receive food and clothing along with resources for health and employment. A coalition of donors helped make the resource center, the first of its kind in DeKalb schools, a reality. Nedra Rhone/[email protected]

This is an important goal at a time when American concerns about immigration are at an all time high. In February, more Americans (28%) ranked immigration as the most important problem facing the U.S., according to a Gallup Poll. The last time immigration topped the list of resident concerns was in 2019, and the percentage of Americans concerned about it is higher than it has been since Gallup began collecting the data in 1981.

The sentiment is likely driven by the high number of southern border crossings in December and the movement of migrants into U.S. cities that has placed a strain on social services. The student population at Dunaire is often a reflection of those patterns. The school had a recent influx of students from Afghanistan and expects there may be an increase in the number of students from Haiti, Deas said.

About 20% of the students are homeless and many live in extended stay motels in the area. Though the community is transient, some families seek stability in the neighborhood so their children can continue learning at Dunaire, Robinson said.

When she conducted a survey to find out what parents needed most, the results were medical support, GED services and employment resources. The school district was planning to move an empty, unused trailer from the school campus but Robinson asked Deas if they could keep it and turn it into a parent resource center. Deas agreed but how could they do it with zero dollars?

Sue Sullivan was doing outreach through Decatur YMCA at a local extended stay motel when she met a parent from Dunaire. The parent kept mentioning Sullivan’s name to Robinson. When the two finally met and Sullivan visited Dunaire, the quiet and calm mood in the building and the melting pot of students from 29 different countries worked its charms. Sullivan began corralling resources and writing grants to help make the trailer happen.

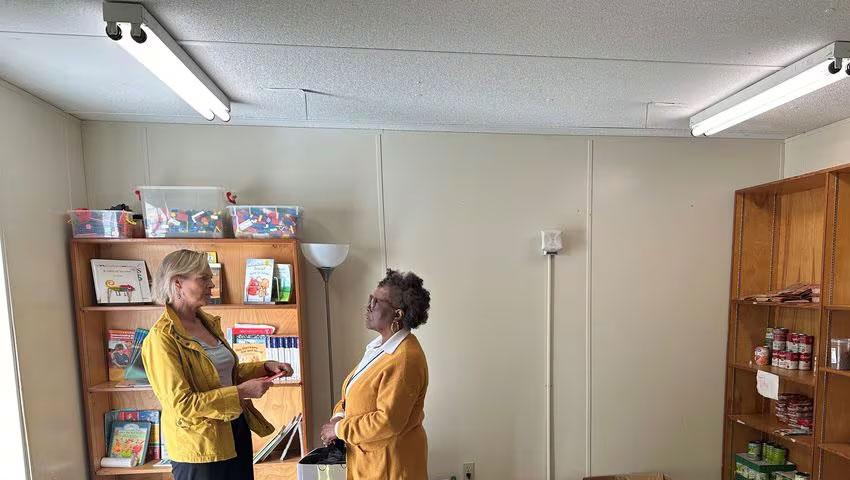

Sue Sullivan (L) and Justine Robinson chat inside the C.A.F.E. at Dunaire Elementary School in Stone Mountain. The C.A.F.E. is a repurposed trailer designed to serve as a resource center for parents and the community which includes immigrant families from at least 29 different countries. Nedra Rhone/[email protected]

That included calling Chastain Clark, an Atlanta-based artist whose business model includes balancing pro bono work with paid projects. Clark, who enjoys exposing young kids to art and engaging them in the many aspects of planning and budgeting a large scale project like a mural, donated his time to design the trailer.

On a recent weekday he painted swirls of blue on the main image: a woman with emerald green eyes trained upward at the sky with a look of joy and hope. The inspiration came from photos of real parents and students in the community. The blue color of the trailer, he says, is calming — and hopefully a welcome sight to those who have journeyed from their home countries to this community.

“I want people who work here to be proud and I want the kids to be proud,” he said. “It is likely the first time they have seen themselves in something they admire.”

Inside, the trailer offers food, clothing, books for children and work resources. Robinson hopes to add dividers to create separate spaces for training and other programming. Already Robinson and the team of C.A.F.E. collaborators have offered employment services and GED assessments but they hope to have more consistent hours (including weekends) and events by early May.

Our schools and communities are a microcosm of the larger society, and the collaborators at Dunaire, in an effort worthy of recognition, have made it a priority to create a safe space where everyone feels a sense of safety and belonging.