Many homeowners are paying a total of billions of dollars extra because of inequities in assessing property values.

Illustration by Nicholas Konrad/The New York Times

Illustration by Nicholas Konrad/The New York Times

By The Editorial Board

The editorial board is a group of opinion journalists whose views are informed by expertise, research, debate and certain longstanding values. It is separate from the newsroom.

Americans expect to pay property taxes at the same rates as their neighbors. But across most of the United States, flat-rate property taxation is a sham.

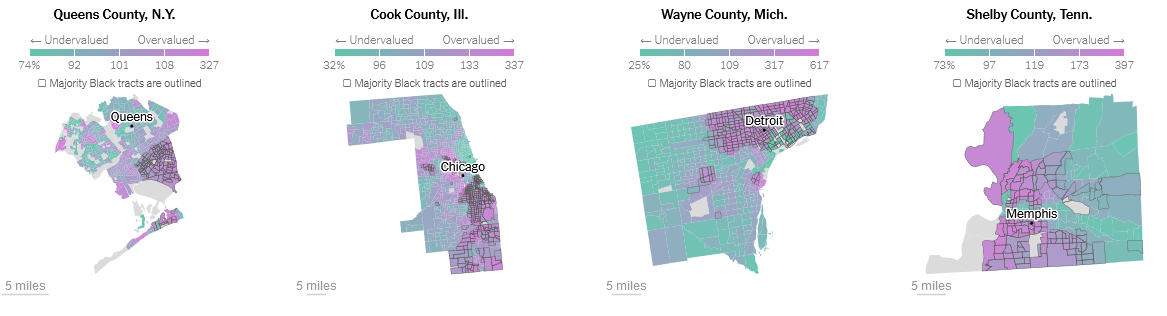

Local governments are failing at the basic task of accurately assessing property values, and there is a clear and striking pattern: More expensive properties are undervalued, while less expensive properties are overvalued. The result is that wealthy homeowners get a big tax break, while less affluent homeowners are paying a higher price for the same public services.

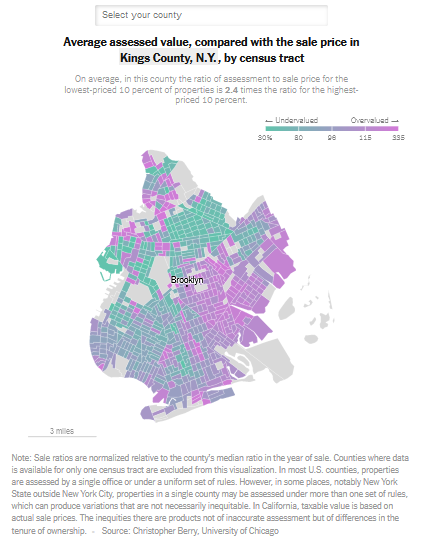

Across the nation, lower-priced homes are assessed at a higher value relative to their actual sale price.

Average assessed value, compared with the sale price

This is true for big cities…

Homeowners have long complained about inequitable assessments, and past studies have documented problems in particular cities. A new nationwide analysis led by Christopher Berry of the University of Chicago reveals that the inequities in tax assessments are both very large and very common.

Homeowners have long complained about inequitable assessments, and past studies have documented problems in particular cities. A new nationwide analysis led by Christopher Berry of the University of Chicago reveals that the inequities in tax assessments are both very large and very common.

For example, in Cook County, Ill., which includes Chicago, 1,015 homes were sold for exactly $100,000 from 2007 to 2016. Their average assessed value before the sale was $151,585. During the same decade, 149 homes sold for exactly $1 million. Their average presale assessed value: $647,030.

These distortions in assessed values carry through directly to tax bills. Nationwide, from 2007 to 2016, homes in the bottom 10 percent of property values in a given county were taxed, on average, at an effective rate that was twice as high as the rate for homes in the top 10 percent of property values.

The maladministration of property taxation means the wrong people are picking up the tab for public services. In a separate study, focused on Cook County, Mr. Berry calculated that from 2011 to 2015, inequities in property assessment resulted in the improper billing of $2.2 billion in taxes. While a comparable national figure is hard to calculate, the scale of the issue is indicated by the fact that local governments annually collect almost $500 billion in residential property taxes.

Inequitable assessment is also an important reason the burden of state and local taxation is regressive, meaning that most state and local governments collect a larger share of the income of lower-income households than of upper-income households. By failing to properly assess property, government is worsening the large and growing inequalities in the distribution of wealth and income.

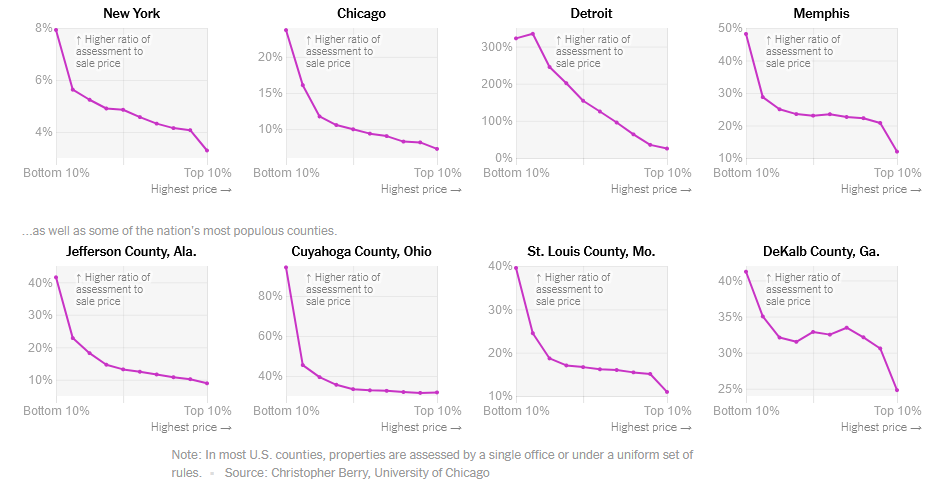

The burden falls disproportionately on minorities. Because of the accumulated effects of past racism, minorities tend to live in homes that command lower prices — yet are assessed at inflated values. In another recent national study of assessment data, the economists Carlos Avenancio-León of Indiana University, Bloomington, and Troup Howard of the University of Utah, found that Black and Hispanic homeowners paid 10 percent to 13 percent more in property taxes than the owners of similar homes living under the same tax laws. For the median minority homeowner, the extra tax tab was more than $300 a year.

Property taxation is appealingly simple in concept: Everyone who owns the same kind of property in the same community pays a fixed share of the value each year to support public schools, public safety, road construction and the other basic functions of local government.

In practice, it’s not so easy to figure out what a home might be worth. Taxable value is an approximation of market value — the amount a buyer would pay. But less than 5 percent of homes are sold in any given year, so assessors need to assign values to every house based on the prices of those few that sold. This is particularly difficult at the fringes of the market.

Both cheap and expensive homes are, by definition, unusual. But even similar homes, as in a cookie-cutter subdivision, are not so easy to assess. A new kitchen can push up the value of one home while an old roof can depress the value of another. And sales prices can be distorted by motivated sellers or eager buyers.

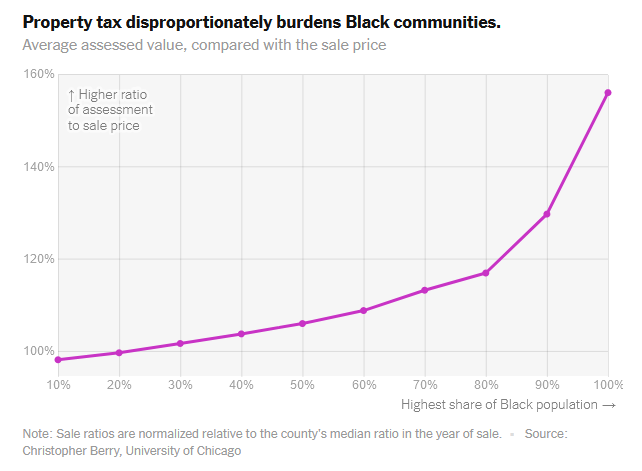

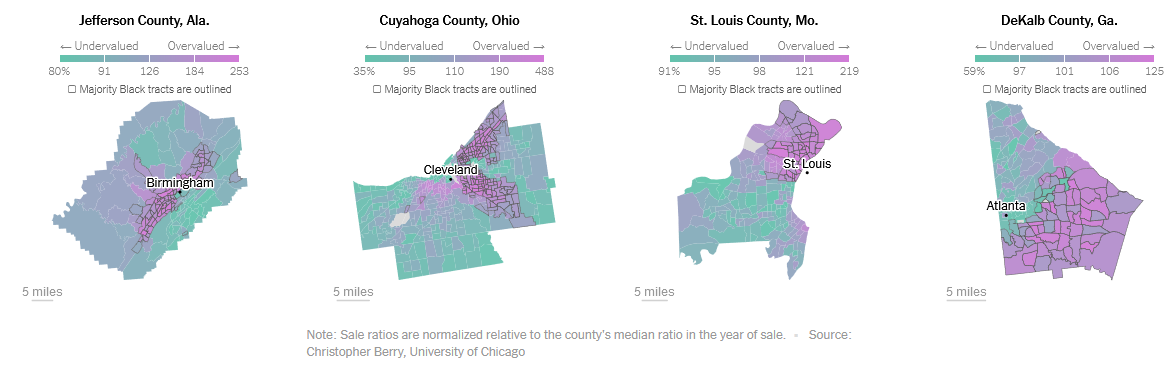

In many areas, property in predominantly Black neighborhoods is overvalued for tax purposes.

Average assessed value, compared with the sale price, by census tract

Some local governments, like Harris County, Texas; Maricopa County, Ariz.; and Wake County, N.C., regularly overcome these obstacles, showing equity is achievable.

But they are exceptions. Mr. Berry examined counties in each year from 2007 to 2016 in every state except California, which has a unique property tax system. In the average year, 90 percent of those counties failed to meet a basic industry standard for accuracy and equity.

Many states require assessors to assess the accuracy of their own results. The problem is what happens next — or, rather, what does not happen next.

In New York, where assessments are mostly performed by cities and towns, the state’s most recent review in 2019 concluded that 55 percent of jurisdictions did not meet the industry standard. But the standard is not enforced. Indeed, New York is one of a small handful of states that does not even require regular assessments.

In Syracuse, which last conducted a citywide assessment in 1996, the city ignored the appreciation of many high-dollar homes until the local paper, The Post-Standard, called attention to the problem. The paper highlighted the example of a woman who paid higher annual taxes on a home she bought for $46,000 than other residents paid for homes purchased at prices that approached $200,000.

In Delaware, where counties have not revalued properties since the 1980s, a state judge ruled last year that inequities had grown so large as to violate the state Constitution.

Reassessment by itself, however, is insufficient if the methodology is warped. In 2017, Detroit systematically updated the values of properties for the first time in six decades, sharply reducing valuations across the board. But an independent review found that high-value homes got disproportionate reductions, deepening inequities.

One reason for these inequities is that assessors aren’t paying enough attention to the cardinal rule of real estate: location, location, location. The data show errors in valuation tend to cluster geographically. Underestimating the significance of location has the effect of discounting the value of properties in more desirable locations and overstating the value of those in less desirable locations.

Some reasons are fairly easy to identify, like the boundaries of school districts. Others, like proximity to a particular house of worship, may be harder to discern. But assessors don’t need to figure out these details. Statistical techniques are readily available to account for variations without inquiring into causes.

Daniel McMillen, a professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago, who has reviewed the recent studies, said that the geographical pattern of the errors indicates that many assessors simply aren’t trying very hard to deliver accurate numbers. Mr. Berry estimates that statistical best practices could reduce the inequities by roughly one-third.

Assessors face a more difficult task in accounting for differences inside homes. Robert Ross, a data scientist who has led an effort to improve Cook County’s assessments, said the county has made significant progress in accounting for location, but still struggles to assess homes in the bottom 30 percent of property values. Using the available data, the county can’t reliably distinguish between a home that will sell for $100,000 and a home that will sell for $150,000. The relevant differences, like new kitchens and old roofs, are often invisible from the street.

Mortgage lenders, whose profits depend on accurate assessments, rely on appraisals that include internal inspections. But emulating that practice would require the consent of the homeowners, and even then it would be dauntingly expensive and politically unpopular.

Fortunately, there are other ways to make progress. Assessors can incorporate data from building permits and real-estate listings. They can make it easier for property owners to submit relevant information. They can seek patterns in the data.

Homestead exemptions, which shelter a portion of the assessed value of a primary residence from taxation, can help to offset the systemic overvaluation of low-end properties. Many homeowners, particularly in lower-income communities, do not claim those exemptions. Local governments can encourage use of the exemptions, or apply them automatically.

Local governments also need to reconsider the process that allows homeowners to appeal assessments. That system is meant to rectify inequities, but it often widens them.

In Nassau County, N.Y., for example, a Newsday investigation in 2017 found that appeals were routinely successful. Following a reassessment, fully 61 percent of property owners won reductions in assessed value. The problem is that those least likely to appeal were the owners of the low-priced properties most likely to be overvalued on the tax rolls.

In Cook County, the nation’s second-largest county by population, Mr. Avenancio-León and Mr. Howard found that minorities were less likely to appeal assessments, that those who appealed were less likely to win and that those who won received smaller assessment reductions.

The inequities that researchers have put on public display are galling not just because they have come at the expense of those who can least afford it, but because it’s clear that it would be relatively easy for local governments to address these problems.

Equitable assessment is possible. Anything less is unacceptable.

Read the original story on NYTimes.com.