Former DeKalb County Commissioner Sharon Barnes Sutton leaves federal court in May, after being released from custody on a $25,000 unsecured bond. Sutton pleaded not guilty to federal charges that she took at least one bribe from a company trying to do business with the county and two counts of extortion. CREDIT: WSB-TV

By Bill Torpy

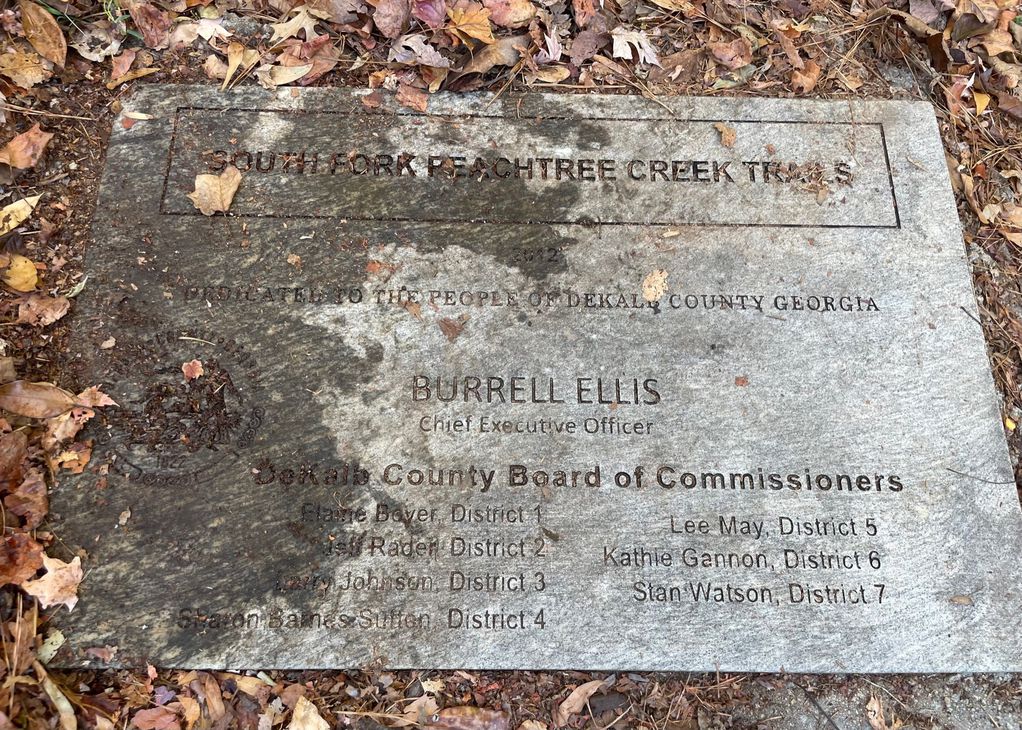

At the entrance of a nature trail near my home, there’s a commemorative stone marking the opening of the path in 2012. Etched into granite are the names of the CEO and seven DeKalb County commissioners from that time — four of whom were later arrested on corruption charges.

It’s almost as if that board could have had a quorum in the pokey. I call the marker The Rock of Shame.

That rock came to mind this week as the federal corruption trial of former DeKalb Commissioner Sharon Barnes Sutton (finally) got underway, nearly six years since she was in office and three years since she was charged.

The trial is the last whimper of an era when DeKalb County was widely seen as a corrupt, inept morass of what government should not be. It was a time of state and federal investigations, of county employees wearing wires and an air of paranoia as officials worried that they might end up on tape.

Even so, some simply could not resist and still dipped into the till. At least that’s what federal prosecutors allege in the case of Barnes Sutton, who was elected in 2008 and bounced from office in 2016 by voters weary of her antics.

The ongoing trial alleges that Barnes Sutton took $1,000 in bribes from a contractor (in the form of two $500 payments) so he could get work on a sewer plant project. Yes, just $1,000. That’s not for a lack of trying, however, as investigators had been looking at her for a couple of years with tapped phones and at least one other wired informant before they netted her in 2014 with the alleged bribe.

A commemorative stone at a DeKalb County nature path denotes a number of public officials who would later get in trouble.

A commemorative stone at a DeKalb County nature path denotes a number of public officials who would later get in trouble.Arf.

Let’s go back a decade to capture the flavor of the time. A $1 billion-plus rebuild of DeKalb’s aging sewer and water system, with all that money and contracts buzzing about, was just too much for some to resist.

Barnes Sutton’s alleged bribes occurred in 2014, a time when almost all of the county’s 750,000 residents knew DeKalb was hip-deep in investigation.

A year earlier, in 2013, a special-purpose grand jury investigating corruption in the water and sewer department issued an explosive report with stories of fictitious contracting companies, suspected payoffs and internal investigations that were squashed.

A story The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote at the time began, “To understand the brazenness of the corruption alleged by a special DeKalb County grand jury, consider this: Officials awarded a $2.2 million-a-year tree-trimming contract to a fake company created by a Cartoon Network employee who didn’t so much as own a chainsaw.”

But the expected roundup of misdoers never really came. Instead, Robert James, the county’s district attorney at the time, focused his energies on then-CEO Burrell Ellis, charging him with shaking down contractors for political contributions. At the base of that investigation was the county’s procurement director at the time, Kelvin Walton, who got snared in the sewer probe and was forced to wear a wire.

Walton then goaded Ellis to anger as the CEO made calls for campaign donations, urging retaliation against those unwilling to contribute to his re-election campaign. It worked, almost too well. Ellis was convicted on corruption charges, did prison time and then had his case overturned by the appeals court after his release. The whole thing carried a whiff of entrapment and didn’t address the stink around the sewer department.

Former Commissioner Stan Watson, who was investigated for all sorts of inventive ways at earning extra cash as an elected official, was finally pinched in 2017 for pocketing about $3,000 in advance money to travel to conferences he never attended. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, got 12 months probation and a fine — and later ran again for office, an open legislative seat. Voters, who by then were in a good government frame of mind, sent him packing.

August 26, 2014 Decatur – DeKalb County commissioners (from left) Jeff Rader, Stan Watson, Larry Johnson, Sharon Barnes Sutton and Kathie Gannon listen during a public comment session at a meeting at Dekalb County Government Administration Building in Decatur on Tuesday, August 26, 2014. A day after resigning from office, DeKalb County Commissioner Elaine Boyer announced in court Tuesday she pleaded guilty to federal charges accusing her of two schemes to pocket tens of thousands of dollars from taxpayers. HYOSUB SHIN / HSHIN@AJC.COM

Former Commissioner Elaine Boyer outdid them all. She was nabbed defrauding the county of at least $83,000 in a kickback scheme in 2014. She served a year.

I called current CEO Mike Thurmond, who was not around at the time and has toiled to keep DeKalb off the front page these past six years. The usually chatty Thurmond politely steered clear of this mess, declining to talk. He has redoubled efforts to fix the water and sewer system, which is still ongoing.

Commissioner Jeff Rader, who was around at the time and is leaving office at year’s end, at his own volition, said DeKalb’s problems were due to “the particular personalities (in office) at the time.”

But, he added, “a lot of the risk factors still exist in DeKalb.” He said the balance of power in the county’s unusual CEO-form government leans to DeKalb’s elected chief, creating an imbalance in power between the administrative branch and the commissioners.

It’s more difficult for commissioners to have a hand guiding public policy, Rader said, “So they tend to look for other things to do.”

He then added, “I don’t think people should think that it will never happen again.”

Read the original story on AJC.com.